I.

A well-known Native American proverb states: “Never criticize a man until you have walked two moons in his moccasins.” This is straightforward advice, yet it can be notoriously difficult to implement. According to social psychologists, we tend to underestimate the role that people’s circumstances play in shaping their behavior. Stanford researcher Lee Ross called this phenomenon the “fundamental attribution error.”[i] It implies that we often judge the actions of others even before we have considered how we might act if we were placed in a similar situation. As a result, we grant the benefit of the doubt less often than we should.

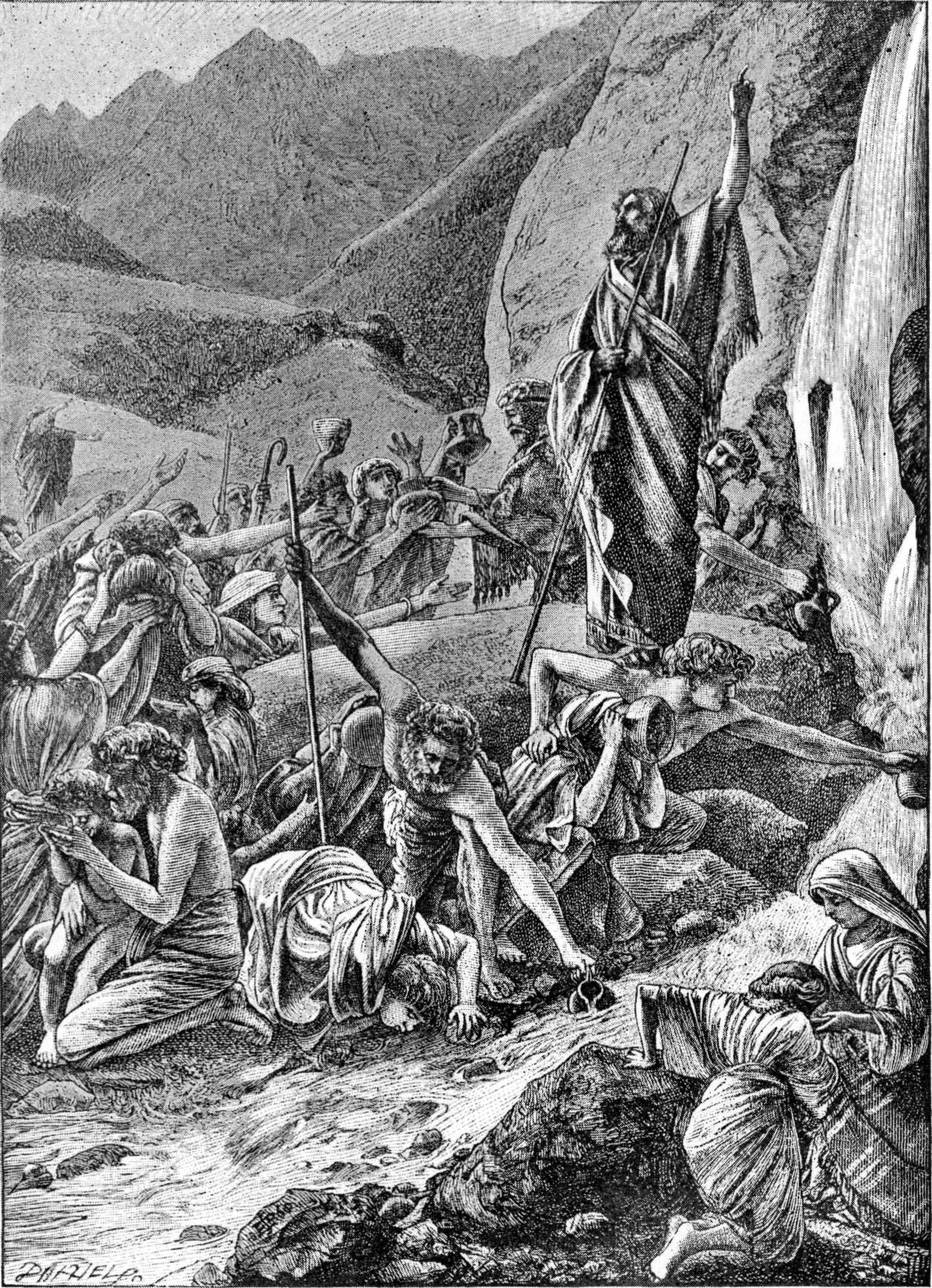

In this article, I would like to show how easy it is to commit the “fundamental attribution error” when we study the story of the “Waters of Merivah.” In the twentieth chapter of the book of Bamidbar, the Israelites petition Moshe over a lack of water. Hashem commands Moshe to “speak to the rock in their presence, and it will give forth its water, and you shall bring forth water for them” (Num. 20:8). But Moshe calls the people “rebels” (20:10) and “strikes the rock with his staff twice” (21:10). In response, Hashem declares: “Since you did not have faith in Me to sanctify Me in the eyes of the children of Israel, therefore you shall not bring this assembly to the Land which I have given them” (21:11).

What exactly did Moshe do wrong at Merivah that caused him to be punished so severely? Scholars have debated this question for centuries.[ii] However, we are going to approach the text from a slightly different perspective. Instead of analyzing how Moshe should or should not have acted during this particular episode—an important line of inquiry in its own right—let us try to think about how he must have felt.

II.

Our chapter opens with a jarring juxtaposition:

The entire congregation of the children of Israel arrived at the desert of Zin in the first month, and the people settled in Kadesh. Miriam died there and was buried there. The congregation had no water; so they assembled against Moshe and Aaron. The people quarrelled with Moshe and Aaron… (Num. 20:1-3).

If we pause the narrative here and think about this sequence of events on a human level, everything that comes next is suddenly cast in a radically new light. Miriam, Moshe’s sister, has passed away. The description of her death is one of the shortest and most matter-of-fact in all of Tanakh. There is no forewarning, no public ceremony and no mourning period. In fact, Moshe and Aaron do not even have a chance to catch their breath. They are barely back from the funeral when the Israelites angrily accost them.

To be sure, the people raise a valid concern: without water, they will die. Yet the manner in which they present the issue is almost callous:

The people quarreled with Moshe, and they said, “If only we had died with the death of our brothers before the Lord” (Num. 20:3).

The Israelites stress how desperate their situation is by belittling the fates of their “dead brothers.” This sort of sensationalism is inappropriate in its own right, but it is even worse when we remember that the person to whom they are speaking just lost his own sibling. The Torah records about a dozen different complaints that the Israelites presented to Moshe throughout his lifetime. Their rhetoric was often dramatic and offensive. Yet never before and never again did their protests include any talk of “dead brothers.” The single instance of this phrase in the entire Torah occurs right after Miriam’s passing.

And the grumbling continues:

[The people pressed further]: “Why have you brought the congregation of the Lord to this desert so that we and our livestock should die there(שם)?” (Num. 20:4).

There are at least two problems with this accusation. The first is a logical problem: The Israelites insinuate that Moshe deliberately led them to a place with no water, as if he is not suffering from the very same thirst that they are. The second is a grammatical problem: Instead of asking “Why did you bring us into this desert to die here?” the Israelites ask “Why did you bring us to this desert to die there?” But where is “there”?

In fact, this is the second verse in our narrative which features an unnecessary use of the word “there.” We have already seen the first verse together:

The entire congregation of the children of Israel arrived at the desert of Zin in the first month, and the people settled in Kadesh. Miriam died there (שם) and was buried there (שם) (Num. 20:1).

This verse would have read more smoothly had it simply stated “ותמת ותקבר שם מרים”—“Miriam died and was buried there.” Perhaps the Torah employs an awkward double-phrase—“Miriam died there and was buried there”—in order to ensure that the import of the nation’s forthcoming complaint is not lost on the reader. “Why did you bring us to this desert to die there,” the people challenge—they are “here,” in the camp, but they are pointing “there,” to the gravesite of Miriam. Their implication: “It is your fault that your sister died. Make sure that we are not next.”

By this point, Moshe and Aaron have heard enough. Thus, they “flee to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting” (Num. 20:6)—this, incidentally, being the last place they had been with Miriam (Num. 11:5). Once there, they fall on their faces, and God’s presence “descends upon them,” just as it had when they were with their sister a few chapters earlier (ibid). Hashem then delivers the following instructions:

Take the staff and assemble the congregation, you and your brother Aaron, and speak to the rock in their presence so that it will give forth its water… (Num. 20:8).

Moshe knows who Aaron is, of course. Nevertheless, Hashem insists upon identifying him as “your brother.” There are only three other times in the Torah where Aaron is referred to by this designation: when his character is introduced to the reader at the burning bush, when he is appointed as High Priest, and when he dies. It is an extremely rare formulation, yet we find it here. Earlier, the Israelites had spoken of “dead brothers.” Now Hashem, who understands Moshe’s pain, attempts to comfort him by reminding him that not all is lost—after all, there is still “your brother Aaron.”

But Moshe is not ready to be comforted. Uncharacteristically, he is angry—a normal stage of grief, according to Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross[iii]—and he gives voice to that anger:

Moshe and Aaron assembled the congregation in front of the rock, and [Moshe] said to them, “Now listen, you rebels, can we draw water for you from this rock?” (Num. 20:10).

This is the first time in the Torah that Moshe resorts to name-calling—and what a curious name he chooses. The word “rebels,” in Hebrew, is pronounced “morim.”But it is written without vowels, and so it also spells the name מרים—Miriam. That, ultimately, is what this whole episode has been about. Externally, Moshe is chastising the people. Yet his inner thoughts never left his sister for a moment.

III.

Only when we realize how central the memory of Miriam is in this story do we appreciate how deeply tragic a story it is. Miriam, in Hebrew, means “bitter waters,” and for Moshe, no waters are bitterer than these “waters of strife” (Num. 20:13). During her lifetime, Miriam had heard Hashem praise Moshe as “the most faithful (א.מ.ן) servant in all My house” (Num. 12:7). These were the last words spoken to her in the Torah. Yet only a few verses after her death, Hashem declares to Moshe: “Since you did not have faith (א.מ.ן) in Me… therefore you shall not bring this assembly into the land that I have given them” (Num. 20:12). Under Miriam’s watchful eye, baby Moshe was rescued from the waters of the Nile—his very name meant “drawn forth from the water” (Exod. 2:10). It is because Moshe does not want to “draw water forth” (Num. 20:10) for the nation he was chosen to lead that he is ultimately stripped of his duties.

There is a lot to learn from the way this story ends. Despite all of the personal troubles that he was battling, Moshe did not escape punishment for failing to guide his people in its moment of crisis. “Leadership is defined by results,” management expert Peter Drucker reminds us[iv]—and the results of Moshe’s leadership in this case might well have been fatal for the thirsting Israelites had Hashem not intervened. Perhaps it is unfair to expect that our leaders sacrifice their private lives in the interest of the collective which they serve. But when the survival of that collective is on the line, there is no alternative. The Torah does not hold back on this point. As much sympathy as we may have for him, a leader who cannot get it together in the toughest of times cannot continue as a leader. There is simply too much at stake.

And yet, it did not have to come to this. As much as Moshe is responsible for mishandling the very difficult situation in which he was placed, the Israelites bear a share of the responsibility for placing him in that situation to begin with. Had they shown a little more sensitivity, a little more empathy, a little more concern for the welfare of their leader, he might have accompanied them into the Promised Land. But instead of working with Moshe, they chose to work against him. Slowly, surely, their caustic criticism wore away at him. The people’s sense of entitlement and lack of gratitude ended the career of the best leader they ever knew.

IV.

Ironically, one of the few people who ever took interest in Moshe’s personal wellbeing was his sister, Miriam. The very first piece of information we receive about her is that it was she who guarded over Moshe after his mother placed him in a wicker basket to save him from the Egyptians. ותחצב אחתו מרחוק לדעה מה יעשה לו, the Torah tells us: “She stood from afar to see what would be done to him” (Exod. 2:4). For most of his life, Moshe was surrounded by people who could see no further than the “here and now.” They expected him to deliver and got on his case the minute he did not. But Miriam took a step back—ותחצב מרחוק. Miriam took into account מה יעשה לו. She paid attention to “what was happening to him”—to the stresses and pressures facing him—and was always on the lookout for ways to alleviate his burden.

ותחצב מרחוק is more than a description of Miriam’s geographical orientation vis-à-vis Moshe. It is an ethical imperative. Public service, the Torah informs us, is not a one-way street. If a community is to thrive, the yoke of concern cannot rest squarely on the shoulders of its leadership. It must be shared by “the followership.”[v] Though we often forget it, leaders also have needs. They also have feelings. Our job is to be there for them just as they are for us. Instead of tearing down, we must build up; instead of pointing fingers when things go wrong, we must offer a hand.

Most of all, we must keep in mind the eternal words of Hillel: “אל תדון את חברך עד שתגיע למקומו”—“Do not judge your friend until you have reached his position” (Avot 2:4). Leaders are also our friends, Hillel reminds us—and we should treat them that way.

[i] Ross, Lee. “The Intuitive Psychologist and his Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attribution Process,” in Berkowitz, Leonard. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 10. New York, NY: Academic Press, 1977.

[ii] See, for instance, Don Isaac Abarbanel’s commentary to this episode, in which he identifies eleven different approaches to our question in the writings of his predecessors. Also recommended is R. Chanoch Waxman’s essay on the topic, “Of Sticks and Stones,” available at: www.vbm-torah.org.

[iii] See Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy and Their Own Families. New York, NY: Scribner, 2003.

[iv] See “Five Reasons Leaders Should Strive For Respect, Not The Liking Of Followers,” available at: www.forbes.com.

[v] See Riggio, Ronald E., et al. The Art of Followership: How Great Followers Create Great Leaders and Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2008.

Moshe Strikes the Rock: Failed Leadership, or Failed “Followership?”

I.

A well-known Native American proverb states: “Never criticize a man until you have walked two moons in his moccasins.” This is straightforward advice, yet it can be notoriously difficult to implement. According to social psychologists, we tend to underestimate the role that people’s circumstances play in shaping their behavior. Stanford researcher Lee Ross called this phenomenon the “fundamental attribution error.”[i] It implies that we often judge the actions of others even before we have considered how we might act if we were placed in a similar situation. As a result, we grant the benefit of the doubt less often than we should.

In this article, I would like to show how easy it is to commit the “fundamental attribution error” when we study the story of the “Waters of Merivah.” In the twentieth chapter of the book of Bamidbar, the Israelites petition Moshe over a lack of water. Hashem commands Moshe to “speak to the rock in their presence, and it will give forth its water, and you shall bring forth water for them” (Num. 20:8). But Moshe calls the people “rebels” (20:10) and “strikes the rock with his staff twice” (21:10). In response, Hashem declares: “Since you did not have faith in Me to sanctify Me in the eyes of the children of Israel, therefore you shall not bring this assembly to the Land which I have given them” (21:11).

What exactly did Moshe do wrong at Merivah that caused him to be punished so severely? Scholars have debated this question for centuries.[ii] However, we are going to approach the text from a slightly different perspective. Instead of analyzing how Moshe should or should not have acted during this particular episode—an important line of inquiry in its own right—let us try to think about how he must have felt.

II.

Our chapter opens with a jarring juxtaposition:

If we pause the narrative here and think about this sequence of events on a human level, everything that comes next is suddenly cast in a radically new light. Miriam, Moshe’s sister, has passed away. The description of her death is one of the shortest and most matter-of-fact in all of Tanakh. There is no forewarning, no public ceremony and no mourning period. In fact, Moshe and Aaron do not even have a chance to catch their breath. They are barely back from the funeral when the Israelites angrily accost them.

To be sure, the people raise a valid concern: without water, they will die. Yet the manner in which they present the issue is almost callous:

The Israelites stress how desperate their situation is by belittling the fates of their “dead brothers.” This sort of sensationalism is inappropriate in its own right, but it is even worse when we remember that the person to whom they are speaking just lost his own sibling. The Torah records about a dozen different complaints that the Israelites presented to Moshe throughout his lifetime. Their rhetoric was often dramatic and offensive. Yet never before and never again did their protests include any talk of “dead brothers.” The single instance of this phrase in the entire Torah occurs right after Miriam’s passing.

And the grumbling continues:

There are at least two problems with this accusation. The first is a logical problem: The Israelites insinuate that Moshe deliberately led them to a place with no water, as if he is not suffering from the very same thirst that they are. The second is a grammatical problem: Instead of asking “Why did you bring us into this desert to die here?” the Israelites ask “Why did you bring us to this desert to die there?” But where is “there”?

In fact, this is the second verse in our narrative which features an unnecessary use of the word “there.” We have already seen the first verse together:

This verse would have read more smoothly had it simply stated “ותמת ותקבר שם מרים”—“Miriam died and was buried there.” Perhaps the Torah employs an awkward double-phrase—“Miriam died there and was buried there”—in order to ensure that the import of the nation’s forthcoming complaint is not lost on the reader. “Why did you bring us to this desert to die there,” the people challenge—they are “here,” in the camp, but they are pointing “there,” to the gravesite of Miriam. Their implication: “It is your fault that your sister died. Make sure that we are not next.”

By this point, Moshe and Aaron have heard enough. Thus, they “flee to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting” (Num. 20:6)—this, incidentally, being the last place they had been with Miriam (Num. 11:5). Once there, they fall on their faces, and God’s presence “descends upon them,” just as it had when they were with their sister a few chapters earlier (ibid). Hashem then delivers the following instructions:

Moshe knows who Aaron is, of course. Nevertheless, Hashem insists upon identifying him as “your brother.” There are only three other times in the Torah where Aaron is referred to by this designation: when his character is introduced to the reader at the burning bush, when he is appointed as High Priest, and when he dies. It is an extremely rare formulation, yet we find it here. Earlier, the Israelites had spoken of “dead brothers.” Now Hashem, who understands Moshe’s pain, attempts to comfort him by reminding him that not all is lost—after all, there is still “your brother Aaron.”

But Moshe is not ready to be comforted. Uncharacteristically, he is angry—a normal stage of grief, according to Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross[iii]—and he gives voice to that anger:

This is the first time in the Torah that Moshe resorts to name-calling—and what a curious name he chooses. The word “rebels,” in Hebrew, is pronounced “morim.”But it is written without vowels, and so it also spells the name מרים—Miriam. That, ultimately, is what this whole episode has been about. Externally, Moshe is chastising the people. Yet his inner thoughts never left his sister for a moment.

III.

Only when we realize how central the memory of Miriam is in this story do we appreciate how deeply tragic a story it is. Miriam, in Hebrew, means “bitter waters,” and for Moshe, no waters are bitterer than these “waters of strife” (Num. 20:13). During her lifetime, Miriam had heard Hashem praise Moshe as “the most faithful (א.מ.ן) servant in all My house” (Num. 12:7). These were the last words spoken to her in the Torah. Yet only a few verses after her death, Hashem declares to Moshe: “Since you did not have faith (א.מ.ן) in Me… therefore you shall not bring this assembly into the land that I have given them” (Num. 20:12). Under Miriam’s watchful eye, baby Moshe was rescued from the waters of the Nile—his very name meant “drawn forth from the water” (Exod. 2:10). It is because Moshe does not want to “draw water forth” (Num. 20:10) for the nation he was chosen to lead that he is ultimately stripped of his duties.

There is a lot to learn from the way this story ends. Despite all of the personal troubles that he was battling, Moshe did not escape punishment for failing to guide his people in its moment of crisis. “Leadership is defined by results,” management expert Peter Drucker reminds us[iv]—and the results of Moshe’s leadership in this case might well have been fatal for the thirsting Israelites had Hashem not intervened. Perhaps it is unfair to expect that our leaders sacrifice their private lives in the interest of the collective which they serve. But when the survival of that collective is on the line, there is no alternative. The Torah does not hold back on this point. As much sympathy as we may have for him, a leader who cannot get it together in the toughest of times cannot continue as a leader. There is simply too much at stake.

And yet, it did not have to come to this. As much as Moshe is responsible for mishandling the very difficult situation in which he was placed, the Israelites bear a share of the responsibility for placing him in that situation to begin with. Had they shown a little more sensitivity, a little more empathy, a little more concern for the welfare of their leader, he might have accompanied them into the Promised Land. But instead of working with Moshe, they chose to work against him. Slowly, surely, their caustic criticism wore away at him. The people’s sense of entitlement and lack of gratitude ended the career of the best leader they ever knew.

IV.

Ironically, one of the few people who ever took interest in Moshe’s personal wellbeing was his sister, Miriam. The very first piece of information we receive about her is that it was she who guarded over Moshe after his mother placed him in a wicker basket to save him from the Egyptians. ותחצב אחתו מרחוק לדעה מה יעשה לו, the Torah tells us: “She stood from afar to see what would be done to him” (Exod. 2:4). For most of his life, Moshe was surrounded by people who could see no further than the “here and now.” They expected him to deliver and got on his case the minute he did not. But Miriam took a step back—ותחצב מרחוק. Miriam took into account מה יעשה לו. She paid attention to “what was happening to him”—to the stresses and pressures facing him—and was always on the lookout for ways to alleviate his burden.

ותחצב מרחוק is more than a description of Miriam’s geographical orientation vis-à-vis Moshe. It is an ethical imperative. Public service, the Torah informs us, is not a one-way street. If a community is to thrive, the yoke of concern cannot rest squarely on the shoulders of its leadership. It must be shared by “the followership.”[v] Though we often forget it, leaders also have needs. They also have feelings. Our job is to be there for them just as they are for us. Instead of tearing down, we must build up; instead of pointing fingers when things go wrong, we must offer a hand.

Most of all, we must keep in mind the eternal words of Hillel: “אל תדון את חברך עד שתגיע למקומו”—“Do not judge your friend until you have reached his position” (Avot 2:4). Leaders are also our friends, Hillel reminds us—and we should treat them that way.

[i] Ross, Lee. “The Intuitive Psychologist and his Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attribution Process,” in Berkowitz, Leonard. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 10. New York, NY: Academic Press, 1977.

[ii] See, for instance, Don Isaac Abarbanel’s commentary to this episode, in which he identifies eleven different approaches to our question in the writings of his predecessors. Also recommended is R. Chanoch Waxman’s essay on the topic, “Of Sticks and Stones,” available at: www.vbm-torah.org.

[iii] See Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth. On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy and Their Own Families. New York, NY: Scribner, 2003.

[iv] See “Five Reasons Leaders Should Strive For Respect, Not The Liking Of Followers,” available at: www.forbes.com.

[v] See Riggio, Ronald E., et al. The Art of Followership: How Great Followers Create Great Leaders and Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2008.