Human beings are blessed with many remarkable faculties. We experience and interact with the world through our five senses and develop an internal intellectual and emotional structure through our minds and hearts. We often intuitively know which faculty to use for particular purposes. We relate to food mainly through our sense of taste and solve math problems with our intellectual capabilities.

What about our relationship with God? Is there a particular human faculty that should be emphasized in our quest to connect with the Absolute? While the Torah certainly mandates the submersion of the entire self into the service of God, is there still room to create a hierarchy of efficacy between our array of faculties? In this essay, I will briefly outline the approach of Habad Hassidism to this question, using the philosophies of Rambam and R. Hayim of Volozhin as foils.

Rambam

Throughout his works, Rambam refers to the intellectual worship of God as the pinnacle of a religious life. In the last chapter of The Guide to the Perplexed, Rambam lists the various levels of attainable human perfection. The fourth and ultimate level, the “true perfection of man” is:

the acquisition of the rational virtues - I refer to the conception of intelligibles, which teach true opinions concerning the divine things. This is in true reality the ultimate end; this is what gives the individual true perfection, a perfection belonging to him alone; and it gives him permanent perdurance; through it man is man[1]

Despite Judaism’s immense system of positive and negative commands, Rambam sets the sights of the religious questor on intellectual perfection. In fact, the entire system of actional mitzvot with all of its breadth and depth is contextualized as a divine lesson plan to enable and engender greater intellectual meditation of God.[2]

Moreover, Rambam identifies the “soul” of a person with one’s cognitive capabilities; it is the ability to think that is the “image of God” which elevates humans above animals.[3] This is to be contrasted with the body, which, while necessary to house the soul, is described as the source of “all [of] man’s acts of disobedience and sins.”[4] It is for this reason that at opposite side of the spectrum from the intellect stands the sense of touch, the most physical and bodily of the senses. Rambam approvingly cites Aristotle that “that this sense is a disgrace to us.”[5]

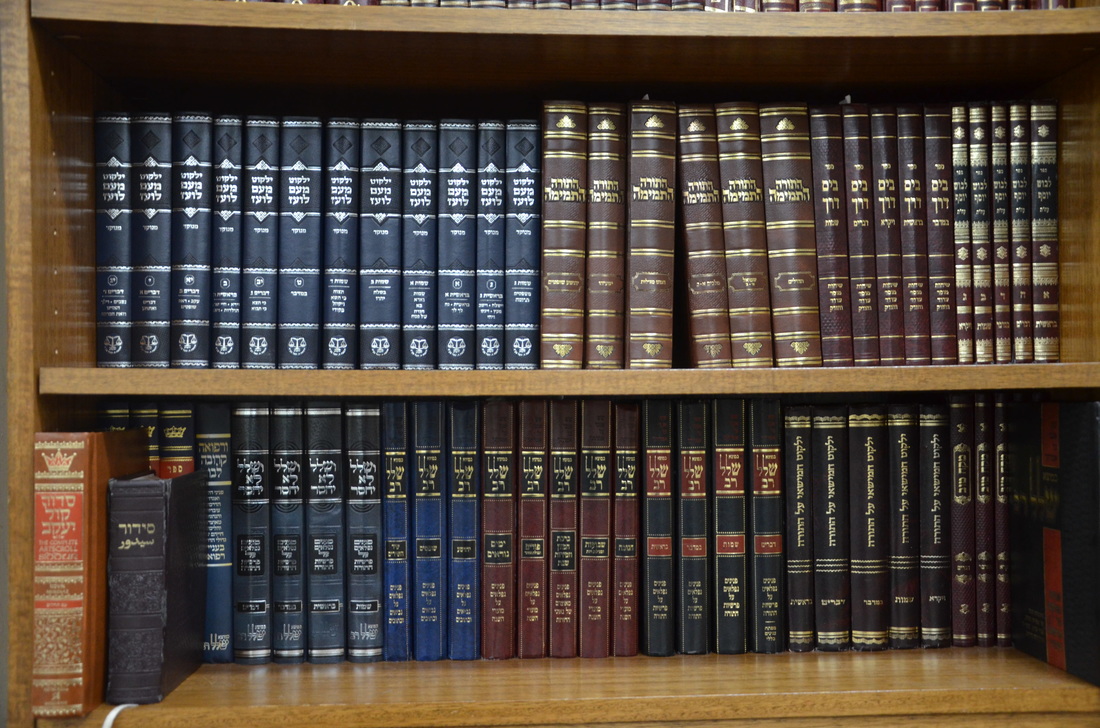

Nefesh ha-Hayim

R. Hayim of Volozhin fundamentally retains the Rambam’s favoritism for the cognitive faculty as the ideal method of connecting with God. However, instead of using one’s intellect to philosophically contemplate God, R. Hayim of Volozhin advocates filling one’s mind with Torah. It is the study of Torah per-se that creates the greatest of all possible bonds with God as “He and His Torah are one.” While God certainly demands the fulfillment of actional mitzvot, their performance cannot compare with the level of connection to God that is engendered by the study of Torah. This is the meaning of the famous Mishnaic dictum “The study of Torah is the equivalent of all of them.”[6]

The Alter Rebbe

R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the Alter Rebbe of Habad, developed a complex relationship between the study of Torah and the fulfillment of actional mizvot. A cursory read of certain passages would indicate that he is in full consent with R. Hayim of Volozhin regarding the supremacy of intellectual study of Torah over the performance of mitzvot. In an early chapter of Tanya, the Alter Rebbe posits a unity between God and His wisdom (the Torah) and a unity between the knower of knowledge and the knowledge itself. Employing a form of the transitive property, the Alter Rebbe asserts that if a person understands the Torah he becomes unified with God’s wisdom which, in essence, translates into a unity with God himself. The result is ”a wonderful union, like which there is none other, and which has no parallel anywhere in the material world.”[7]

However, three interrelated points mitigate this lopsided superiority of intellectual Torah study over action.[8] First, elsewhere in Tanya the Alter Rebbe describes an advantage of actional mitzvot over the study of Torah. While Torah study draws divinity into one’s cognitive and (speaking) faculties, the ultimate mission is to have one’s entire being enveloped in the divine light. It is only the actional mitzvot that are performed by the bodily limbs that allow for divinity to extend even to the body, which is generally associated with man’s baser desires and animalistic soul.[9] In the words of the Alter Rebbe:

Therefore, when a person occupies himself in the Torah, his neshamah, which is his divine soul, with her two innermost garments only, namely the power of speech and thought, are absorbed in the Divine light of the blessed En Sof, and are united with it in a perfect union…. However, in order to draw the light and effulgence of the Shechinah also over his body and animal soul, i.e. on the vital spirit clothed in the physical body, he needs to fulfil the practical commandments which are performed by the body itself…. the energy of the vital spirit in the physical body, originating in the kelipat nogah, is transformed from evil to good, and is actually absorbed into holiness like the divine soul itself.[10]

It is the physical action of a mitzvah that transforms the evil of the body and animal soul into a sanctified entity.[11]

A second element of the Alter Rebbe’s approach to the relationship between Torah study and actional mizvot is that it shifts along the axis of time. He teaches of a unique divine revelation in each generation, causing the people in different eras to primarily focus on a certain aspect of the divine service. While in the times of the tannaim and amoraim the primary divine service was through Torah study, this shifted to prayer in the post-Hazal epoch. As history marched forward and the 19th century arrived, the Alter Rebbe saw another major alteration: “in these generations, the main revelation of God is in the performance of acts of lovingkindness.”[12]

This sentiment is further elucidated in a fundraising letter he wrote to his Hassidim on behalf of their brethren in Israel:

Therefore, my beloved, my brethren: set your hearts to these words expressed in great brevity… how in these times, with the advent of the Messiah, the principal service of G‑d is the service of charity, as our sages, of blessed memory, said: “Israel will be redeemed only through charity.” Our sages, of blessed memory, did not say that the study of Torah is equivalent to the performance of loving-kindness except in their own days. For with them the principal service was the study of Torah and, therefore, there were great scholars: Tannaim and Amoraim. However, with the advent of the Messiah… there is no way of truly cleaving unto it and to convert the darkness into its light, except through a corresponding category of action, namely the act of charity.[13]

The Rabbinic statements regarding the primacy of Torah study over actional mitzovt were primarily directed towards earlier generations.[14] As we approach the messianic era, the focus of our service needs to shift towards sanctifying the lower elements of the world and “converting darkness to light” which requires a new focus on bodily involvement in mitzvot.[15]

It is not random that actional mizvot intended to purify the lower elements of the world become the primary form of service in the pre-messianic era. In several passages, the Alter Rebbe develops a paradoxical and inverted hierarchy of spirituality. Whatever is revealed to us as “lower,” i.e. more physical and less spiritual, is, in fact, rooted in a higher aspect of divinity. This radical idea is often expressed with the phrase “sof ma’aseh be-mah’shavah tehilah” and very fittingly impacts the Alter Rebbe’s conceptualization of physical actions’ significance.[16]

It is natural to assume that Torah study, which absorbs the studier’s “higher” cognitive faculties, is the ideal path of connecting with God. However, the Alter Rebbe posits that while from a certain perspective this remains true, the seemingly contradictory, but, in-reality, complementary,[17] perspective of sof ma’aseh be-mah’shavah tehilah paradoxically teaches that it is bodily involvement with actional mizvot that bind a person with the most essential aspect of divinity. Using kabbalsitic terminology, the Alter Rebbe argues that understanding the Torah connects one with the Hokhmah of God, while physical, actional mizvot involving material items are rooted in the higher element of God’s Razon (will).[18]

In summary, while Rambam and R. Hayim of Volozhin assumed a constant hierarchy between intellectual and actional service that is weighted towards the former, the Alter Rebbe developed a multi-tiered approach. The intuitive perspective grants Torah study primacy over the fulfillment of actional mizvot. However, an equally valid and complementary viewpoint creates a system in which actional mizvot are also a means of connecting with the most elemental aspect of divinity. It is this latter form of worship that has the ability to purify even the lower aspects of the world in anticipation for the coming of Mashiach.[19]

Lubavitcher Rebbe

R. Menahem Mendel Schneerson, (henceforth the Lubavitcher Rebbe) took his predecessor’s idea, expanded it and applied it. His frequent mantra “ha-Ma’aseh Hu ha-Ikar”[20] was not just a rallying cry to galvanize his followers but reflected an acute implementation of the Alter Rebbe’s emphasis on ma’aseh as the world readied for redemption.[21]

While for the Alter Rebbe, the primary meaning of “action” was the simple performance of mizvot and especially charity, the 7th Rebbe emphasized the need to encourage these actions even in the “lowest” realms, far from the hallowed halls of the beit midrash and synagogue. Such a service requires self-sacrifice on the part of the practitioner who would be naturally more inclined to remain safely within the spiritual oasis of his devout fraternity. Paradoxically, however, it is only through overcoming the revealed and natural desire for perceived spiritualty to instead engage in “lowly” physical mizvot in the “lowest” realms, that one can draw the highest levels of divinity into the world.[22]

The following siha of the Lubavitcher Rebbe is paradigmatic of his unique approach to this topic. On Shabbat parshat Vayeitzei 5740[23] the Lubavitcher Rebbe dedicated his address to Yaakov’s life trajectory. We are taught that Yaakov spent his early years in the tent of Torah, but as a mature adult he is forced to flee to the house of Lavan where his life becomes pervaded with sheep. He shepherds Lavan’s sheep for twenty years, becomes wealthy through the sheep business, experiments in sheep-breeding procedures and even dreams about sheep. What is the deeper significance in this transition from Torah study to sheep?

The Rebbe began his explanation by citing a midrash that has a dual description of our relationship with God:

He will be a Father to me and I will be a son to Him…. He will be a Shepherd to me… and I will be sheep to Him.”[24]

This midrash is initially perplexing. After underscoring the unique love between Hashem and the Jewish people through analogizing the Jewish people as Hashem’s child, what is to be gained by referring to us as Hashem’s sheep? Surely a father loves his child more than the shepherd loves his sheep?

The Rebbe explained that children and sheep represent two layers in our connection and service to Hashem. The parent-child relationship is the deepest bond that can exist between two entities, but it remains as just that - a bond between two separate entities. For all the natural love and closeness that they feel for each other, the child is an autonomous human being with his own mind. On this level, a Jew, as an independent person, is privileged to have an incredible, loving, bidirectional relationship with God. Our service stems from a desire to please the Ultimate Being that we love.

While a sheep is certainly less cherished than a child, from a different perspective the sheep-shepherd relationship runs even deeper than the child-parent. Of all animals, sheep are characterized by their obedience and submission. A sheep does not heed the shepherd’s call from a desire to please the shepherd, but rather due to its obedient nature. For a Jew, this level of self-negation (bittul) stems from the realization of ain od milvado, that nothing, especially one’s soul, exists outside of God. Therefore, we are truly not independent entities and have no will outside of God.

These two levels of connection to God are associated with two different forms of service. Torah study corresponds to the level of the child. The strong intellectual effort that is expended on Torah study highlights the reality of the studier as an independent person with an autonomous and creative mind. Also, it is through Torah study that we recognize God’s grandeur, which generates our love for Him and desire to please Him. In this sense, we are similar to the child seeking to please his “great” parent whom he loves.

The self-negation of a sheep rises to the fore when we are involved in actional mitzvot intended to purify the world. The Hebrew word for sheep, zon, is etymologically connected with the word Hebrew word yezi’ah or “going out.” The mission of purifying the world requires one to leave the spiritual sweetness of the study hall and “go out” to be physically involved with the less “spiritual” broader world. This transition entails a double descent: from the study hall to the outside world and from a focus on one’s more “spiritual” intellectual faculties to an involvement in the world of action. For the average person interested in developing a bidirectional relationship with God, such a shift would be assessed as a spiritual regression.

It is only a person who is completely nullified to God that will be willing to sacrifice his own feelings of spirituality for the sake of God’s mission.[25] It is this kind of selfless service that most fully creates the dirah be-tahh’tonim (dwelling place in the lowest realms) for God.[26]

This, then, explains the course of Yaakov’s life. He begins as a son of God who studies Torah in the tents of Shem and Ever, far from the troubles and travails of the world. But it is only after “va-yeizei Ya’akov,” when Yaakov leaves his familiar spiritual surroundings and goes to Haran that he develops the deeper connection with Hashem through bittul. It is paradoxically not the study of Torah per-se, but rather his honesty and integrity in business and the actual performance of the six hundred and thirteen commandments in Lavan’s house that allows Yaakov and the whole world to achieve the ultimate connection with Hashem. It is for this reason that sheep, symbolic of the service through self-nullification, become the leitmotif in Yaakov’s life after leaving his father’s home.

The Rebbe concluded that this lesson is particularly pertinent in this generation:

The obvious directive that results from the above (in our generation) is: We must carry out the order of Divine service [related to Parshas] Vayeitzei[that focuses on] going out to the world and illuminating it. Before this, one must prepare by studying Torah in the tents of Shem and Ever. But to attain [the peak of] “And the man became exceedingly prosperous,” i.e., “fill[ing] up the land and conquer[ing] it,” one must go out to the world and occupy himself with illuminating it.[27]

On the contrary, in this era of ikvesa diMeshicha, when Mashiach’s approaching footsteps can be heard, the primary dimension of our Divine service is deed. This differs from the era of the Talmud, when Torah study was the fundamental element of Divine service. This is reflected in the ruling of the Shulchan Aruch, that there is no one in the present age of whom it can be said: “his Torah is his occupation” (as was the level of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his colleagues). Not even a small percentage of the Jewish people are on that level, because the fundamental Divine service of the present era is deed, actual tzedakah.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe further emphasizes that this newfound focus on action for the sake of illuminating the lowest aspects of the world needs to be characterized by the utmost sense of self-negation:

To add another point: In order that one’s efforts will find great success, they must be carried out in a manner of bittul. They must be carried out for the sake of fulfilling G‑d’s mission of illuminating the exile.

When one carries out his mission with bittul, his efforts are not correspondent to the limits of his nature and satisfaction. It does not make that much difference to him where G‑d sends him.

For the Lubavitcher Rebbe, this emphasis on ma’aseh affects even the motivation and mode of Torah study. In the ideal messianic setting, one’s learning does not only express an autonomous and creative mind, but must simultaneously and paradoxically be executed with a complete sense of bittul, which generally typifies action.[28] The unification of these seemingly antithetical modes of worship can only occur when the deepest essence of the neshama is accessed, a level that is associated with the messianic era.[29]

The Lubavitcher Rebbe saw this shift toward “ma’aseh gadol” as part of a more general recalibration in emphasis of our avodat Hashem as we approach the messianic era. Many of the ideas that were previously esoterically expressed in Habad’s voluminous literature were not only expansively and innovatively developed by the Rebbe during his forty year tenure as Habad’s leader, but also took on greater physical and practical form.

May we merit to properly serve God with our minds, hearts and actions.

[1]Guide to the Perlplexed, 3:54. Translation from Shlomo Pines, Guide to the Perplexed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), 635.

[2] Marvin Fox, Interpreting Maimonides (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990), 316-317; Norman Lamm, Torah Lishmah: Torah for Torah’s Sake in the Works of Rabbi Hayyim of Volozhin and his Contemporaries (Hoboken, New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House; New York, Yeshivah University Press, 1989), 143; Menahem Kellner, Science in the Bet Midrash: Studies in Maimonides (Brighton MA: Academic Studies Press, 2009), 63-80. See Guide to the Perplexed, 3:27 where this point is made most explicitly. Lamm, Torah Lishmah, 174 notes that his assertion that Rambam unequivocally favors intellectual enlightenment to observance of the halakhic system is challenged by Dr. Isadore Twersky in his Introduction to the Code of Maimonides.

[3] Yesodei HaTorah 4:8

[4] Guide to the Perplexed 3:8 (Pines, 431).

[5] Guide to the Perplexed 2:56 (Pines, 371) and 3:8.

[6] All of Section 4 of Nefesh ha-Hayim is dedicated to the nature and significance of Torah study. For R. Hayim’s understanding of the relationship between Torah study and the fulfillment of actional mizvot, see 4:29-30. For analysis and contextualization see Lamm, Torah Lishmah, 153-154.

[7] Tanya, Likkutei Amarim, chapter 5. Translation from http://www.chabad.org/library/tanya/tanya_cdo/aid/1028886/jewish/Chapter-5.htm.

[8] See Moshe Halamish, Mishnato ha-Iyunit shel R. Shneur Zalman mi-Liadi, Dissertation (Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, 1976), 244-272 for an elaboration on many of these themes.

[9] Tanya, Likkutei Amarim, chapter 1.

[10] Tanya, Likkutei Amarim, chapter 35. Translation from http://www.chabad.org/library/tanya/tanya_cdo/aid/1029034/jewish/Chapter-35.htm.

[11] See, also, Tanya, Iggeret ha-Kodesh, epistle 5.

[12] Torah Ohr, Ester, 120b.

[13]Tanya, Iggeret ha-Kodesh, Epistle 9. Translation from http://www.chabad.org/library/tanya/tanya_cdo/aid/1029292/jewish/Epistle-9.htm. See, ibid, Epistle 5 for the explanation of why charity in particular is the paradigmatic actional mitzvah.

[14] It is interesting that a parallel to this historical shift can be found in the individual person. There is a tannaitic debate (Kiddushin 40b) regarding which of Talmud or ma’aseh is “greater.” Shitah Mekubezet, Bava Kamma 17a cites the opinion of R. Yeshaya that during one’s youth, Talmud is greater, but “in the end of a person’s life” we assume that ma’aseh is greater.

[15] It is passages such as these that presumably served as sources for Rav Kook’s perspective that certain emphases in the service of God need to be recalibrated as the messianic process accelerates. See my recent article “’She Should Carry Out All Her Deeds According To His Directives:’ A Halakha in a Changes Social Reality” at Lehrhaus for a case study and brief elaboration on this theme in the thought of Rav Kook.

[16] See Jerome Gellman, “Zion and Jerusalem” in Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and Jewish Spirituality ed. Lawrence Kaplan and David Shatz (New York: New York University Press), 288 who lists fourteen distinct places where this idea appears in the thought of the Alter Rebbe.

[17] Habad Hassidism never shied away from a dialectical embrace of seemingly contradictory notions, and in fact, these paradoxes are at the core of the Habad world view. See, Rachel Elior, The Paradoxical Ascent to God: The Kabbalistic Theosophy of Habad Hassidism, trans. Jefferey Green, (SUNY Press, 1992), 33-35 who lists a series of core paradoxes that lie at the heart of Habad doctrine.

[18] Torah Ohr, Parshat Noah, 8c. For an explanation of the terms Hokhmah and Razon see Nissan Dubov, “The Sefirot,” available at http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/361885/jewish/The-Sefirot.htm. Another very relevant primary source appears in his Seder Tefilot mi-Kol ha-Shanah Volume 1, 23a where the Alter Rebbe connects the unique relevance of action for the later generations with the fact that action is rooted in the highest level of divinity. It is also important to note that the performance of mizvot in this system is an end unto itself and not a means towards a higher goal as there can be no further regression beyond God’s Will. In this regard, see, Likkutei Sihot Volume 6, pg. 21-22 and notes 69-70 there.

[19] It is important to note that the relationship between Torah study and action in the thought of the Alter Rebbe is a disputed matter in scholarship. My above presentation follows which did not present the Alter Rebbe as categorically favoring actions over learning is the approach of Moshe Halamish, “Mishnato ha-Iyunit shel R. Shneur Zalman mi-Liadi” 269-271. He marshals many conflicting statements regarding the hierarchy of Torah study and actional mizvot and therefore concludes that in the Alter Rebbe’s final estimation one cannot speak of a true hierarchy but of complementary perspectives. I was recently informed that this is also the internal tradition of Habad Hassidim. However, see Norman Lamm, Torah Lishma, 147-151 and Rivkah Schatz Uffenheimer, “Anti Spiritualizm she-be-Hassidut: Iyunim be-Torat Shen’ur Zalman mi-Liadi” ha-Molad 171-172 (1953): 513-528 who assert that that ultimately the Alter Rebbe gave action a higher place in the spiritual hierarchy than Torah study. In this regard it is enlightening to read the siha of the 7th Lubavitcher Rebbe (Likkutei Sihot, Volume 8, 186-191) who proposes that while only actions can draw down from the “essence” of God, Torah study is necessary in order to reveal the “Divine essence” in this world.

[20] See Avot, 1:17. Also, regarding the tannaitic debate (Kiddushin 40b) if Talmud or ma’aseh is “greater,” see Sefer ha-Ma’amarim 5747, pg. 58 where the Rebbe posits that throughout most of history the ruling has been on the side of Talmud (though, see Rashi, Bava Kama 17a s.v. meivi lidei), in the times of Mashiach the Sanhedrin will reverse the ruling and decide that ma’aseh is “greater.” See there for a longer analysis.

[21] It is interesting that the Vilna Gaon also spoke of the increased significance of action as part of the messianic process, as least in regard to the “ma’aseh” of settling the Land of Israel. See, Kol ha-Tor chapter 1 and Refael Shohat, Olam Nistar be-Mamadei ha-Zeman: Torat ha-Geulah shel ha-Gra mi-Vilna, Mekoroteha, ve-Hashpa’atah le-Dorot (Ramat Gan: University of Bar Ilan Press, 2008), 239-242. Rav Kook (Shemonah Kevazim 3:92), as well, discusses the newfound crucial nature of “ma’aseh,” in the form of engaging worldly affairs, during the era preceding the coming of Mashiach.

[22] For a longer discussion of this topic see R. Feital Levin, Heaven on Earth: Reflections on the Theology of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menahem M. Schneerson (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot Publishing Society, 2002), 114-122; Yizhak Krauss, ha-Shevi’i – Meshi’hiyut be-Dor ha-Shevi’i shel Habad (Tel Aviv: Yedi’ot Ahronot Books, 2007), 137-143.

[23] Likkutei Sihot Volume 15, 252-258.

[24] Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah 2:16.

[25] For a detailed elaboration of the various levels of mizvot in the thought of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, see Gidran shel Mizvot, Hukim u-Mishpatim be-Mishnato shel ha-Rebbe, compiled by R. Yoel Kahn (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot Publication Society, 1994). The highest level of the performance of mizvot in the state of complete bittul is discussed there, pp. 38-43.

[26] The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s association of actional mizvot with complete bittul to God and the study of Torah with a human being’s independent and autonomous nature is a study in contrasts with the approach of Rav Soloveitchik. See, Maimonides: Between Philosophy and Halakha: Rabbi Joseph b. Soloveitchik’s Lectures on the Guide to the Perplexed at the Bernard Revel Graduate School (1950-1951) edited, annotated and with an introduction by Lawrence J. Kaplan (Brooklyn, NY: Ktav Publishing; Jerusalem, Urim Publications, 2016), 234-235 where Rav Soloveitchik associates the study of Torah with “ontic identification with God,” and the fulfillment of actional mizvot with “the expression of my consciousness of ontic separation [from God].”

[27] Translation is adapted from http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article_cdo/aid/2295019/jewish/A-Knowing-Heart-Parshas-Vayeitzei.htm.

[28] See the following Ma’marim which express this notion: Marg’la be-Phumeih de-Rava, 5740, sections 7-10; ve-Avdi Dovid 5746, sections 4-5. See also, Torat Menahem, 5719 (volume 25), 275-279; 283-285 for a description of the study of Torah that draws the Divine essence into the world.

[29] For an elaboration on this theme, see R. Yoel Kahn, “Hein ke-Vanim, Hein ka-Avadim” in Ma’ayanotekha le-Mah’shevet Habad 2 (Tamuz, 5764): 2-8; “u-She’avtem Mayim be-Sasson” in Ma’ayanotekha le-Mah’shevet Habad 45 (Tishrei, 5776): 2-7. See also, the above siha about Yaakov, section 6 where the Rebbe describes the necessity for even actions to be intermixed with aspects of the worship of a “son.”

Sof Ma’aseh be-Mah’savha Tehilah: Torah Study and Actional Mitzvot in the Philosophy of Ḥabad Hassidism

Human beings are blessed with many remarkable faculties. We experience and interact with the world through our five senses and develop an internal intellectual and emotional structure through our minds and hearts. We often intuitively know which faculty to use for particular purposes. We relate to food mainly through our sense of taste and solve math problems with our intellectual capabilities.

What about our relationship with God? Is there a particular human faculty that should be emphasized in our quest to connect with the Absolute? While the Torah certainly mandates the submersion of the entire self into the service of God, is there still room to create a hierarchy of efficacy between our array of faculties? In this essay, I will briefly outline the approach of Habad Hassidism to this question, using the philosophies of Rambam and R. Hayim of Volozhin as foils.

Rambam

Throughout his works, Rambam refers to the intellectual worship of God as the pinnacle of a religious life. In the last chapter of The Guide to the Perplexed, Rambam lists the various levels of attainable human perfection. The fourth and ultimate level, the “true perfection of man” is:

Despite Judaism’s immense system of positive and negative commands, Rambam sets the sights of the religious questor on intellectual perfection. In fact, the entire system of actional mitzvot with all of its breadth and depth is contextualized as a divine lesson plan to enable and engender greater intellectual meditation of God.[2]

Moreover, Rambam identifies the “soul” of a person with one’s cognitive capabilities; it is the ability to think that is the “image of God” which elevates humans above animals.[3] This is to be contrasted with the body, which, while necessary to house the soul, is described as the source of “all [of] man’s acts of disobedience and sins.”[4] It is for this reason that at opposite side of the spectrum from the intellect stands the sense of touch, the most physical and bodily of the senses. Rambam approvingly cites Aristotle that “that this sense is a disgrace to us.”[5]

Nefesh ha-Hayim

R. Hayim of Volozhin fundamentally retains the Rambam’s favoritism for the cognitive faculty as the ideal method of connecting with God. However, instead of using one’s intellect to philosophically contemplate God, R. Hayim of Volozhin advocates filling one’s mind with Torah. It is the study of Torah per-se that creates the greatest of all possible bonds with God as “He and His Torah are one.” While God certainly demands the fulfillment of actional mitzvot, their performance cannot compare with the level of connection to God that is engendered by the study of Torah. This is the meaning of the famous Mishnaic dictum “The study of Torah is the equivalent of all of them.”[6]

The Alter Rebbe

R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the Alter Rebbe of Habad, developed a complex relationship between the study of Torah and the fulfillment of actional mizvot. A cursory read of certain passages would indicate that he is in full consent with R. Hayim of Volozhin regarding the supremacy of intellectual study of Torah over the performance of mitzvot. In an early chapter of Tanya, the Alter Rebbe posits a unity between God and His wisdom (the Torah) and a unity between the knower of knowledge and the knowledge itself. Employing a form of the transitive property, the Alter Rebbe asserts that if a person understands the Torah he becomes unified with God’s wisdom which, in essence, translates into a unity with God himself. The result is ”a wonderful union, like which there is none other, and which has no parallel anywhere in the material world.”[7]

However, three interrelated points mitigate this lopsided superiority of intellectual Torah study over action.[8] First, elsewhere in Tanya the Alter Rebbe describes an advantage of actional mitzvot over the study of Torah. While Torah study draws divinity into one’s cognitive and (speaking) faculties, the ultimate mission is to have one’s entire being enveloped in the divine light. It is only the actional mitzvot that are performed by the bodily limbs that allow for divinity to extend even to the body, which is generally associated with man’s baser desires and animalistic soul.[9] In the words of the Alter Rebbe:

It is the physical action of a mitzvah that transforms the evil of the body and animal soul into a sanctified entity.[11]

A second element of the Alter Rebbe’s approach to the relationship between Torah study and actional mizvot is that it shifts along the axis of time. He teaches of a unique divine revelation in each generation, causing the people in different eras to primarily focus on a certain aspect of the divine service. While in the times of the tannaim and amoraim the primary divine service was through Torah study, this shifted to prayer in the post-Hazal epoch. As history marched forward and the 19th century arrived, the Alter Rebbe saw another major alteration: “in these generations, the main revelation of God is in the performance of acts of lovingkindness.”[12]

This sentiment is further elucidated in a fundraising letter he wrote to his Hassidim on behalf of their brethren in Israel:

The Rabbinic statements regarding the primacy of Torah study over actional mitzovt were primarily directed towards earlier generations.[14] As we approach the messianic era, the focus of our service needs to shift towards sanctifying the lower elements of the world and “converting darkness to light” which requires a new focus on bodily involvement in mitzvot.[15]

It is not random that actional mizvot intended to purify the lower elements of the world become the primary form of service in the pre-messianic era. In several passages, the Alter Rebbe develops a paradoxical and inverted hierarchy of spirituality. Whatever is revealed to us as “lower,” i.e. more physical and less spiritual, is, in fact, rooted in a higher aspect of divinity. This radical idea is often expressed with the phrase “sof ma’aseh be-mah’shavah tehilah” and very fittingly impacts the Alter Rebbe’s conceptualization of physical actions’ significance.[16]

It is natural to assume that Torah study, which absorbs the studier’s “higher” cognitive faculties, is the ideal path of connecting with God. However, the Alter Rebbe posits that while from a certain perspective this remains true, the seemingly contradictory, but, in-reality, complementary,[17] perspective of sof ma’aseh be-mah’shavah tehilah paradoxically teaches that it is bodily involvement with actional mizvot that bind a person with the most essential aspect of divinity. Using kabbalsitic terminology, the Alter Rebbe argues that understanding the Torah connects one with the Hokhmah of God, while physical, actional mizvot involving material items are rooted in the higher element of God’s Razon (will).[18]

In summary, while Rambam and R. Hayim of Volozhin assumed a constant hierarchy between intellectual and actional service that is weighted towards the former, the Alter Rebbe developed a multi-tiered approach. The intuitive perspective grants Torah study primacy over the fulfillment of actional mizvot. However, an equally valid and complementary viewpoint creates a system in which actional mizvot are also a means of connecting with the most elemental aspect of divinity. It is this latter form of worship that has the ability to purify even the lower aspects of the world in anticipation for the coming of Mashiach.[19]

Lubavitcher Rebbe

R. Menahem Mendel Schneerson, (henceforth the Lubavitcher Rebbe) took his predecessor’s idea, expanded it and applied it. His frequent mantra “ha-Ma’aseh Hu ha-Ikar”[20] was not just a rallying cry to galvanize his followers but reflected an acute implementation of the Alter Rebbe’s emphasis on ma’aseh as the world readied for redemption.[21]

While for the Alter Rebbe, the primary meaning of “action” was the simple performance of mizvot and especially charity, the 7th Rebbe emphasized the need to encourage these actions even in the “lowest” realms, far from the hallowed halls of the beit midrash and synagogue. Such a service requires self-sacrifice on the part of the practitioner who would be naturally more inclined to remain safely within the spiritual oasis of his devout fraternity. Paradoxically, however, it is only through overcoming the revealed and natural desire for perceived spiritualty to instead engage in “lowly” physical mizvot in the “lowest” realms, that one can draw the highest levels of divinity into the world.[22]

The following siha of the Lubavitcher Rebbe is paradigmatic of his unique approach to this topic. On Shabbat parshat Vayeitzei 5740[23] the Lubavitcher Rebbe dedicated his address to Yaakov’s life trajectory. We are taught that Yaakov spent his early years in the tent of Torah, but as a mature adult he is forced to flee to the house of Lavan where his life becomes pervaded with sheep. He shepherds Lavan’s sheep for twenty years, becomes wealthy through the sheep business, experiments in sheep-breeding procedures and even dreams about sheep. What is the deeper significance in this transition from Torah study to sheep?

The Rebbe began his explanation by citing a midrash that has a dual description of our relationship with God:

This midrash is initially perplexing. After underscoring the unique love between Hashem and the Jewish people through analogizing the Jewish people as Hashem’s child, what is to be gained by referring to us as Hashem’s sheep? Surely a father loves his child more than the shepherd loves his sheep?

The Rebbe explained that children and sheep represent two layers in our connection and service to Hashem. The parent-child relationship is the deepest bond that can exist between two entities, but it remains as just that - a bond between two separate entities. For all the natural love and closeness that they feel for each other, the child is an autonomous human being with his own mind. On this level, a Jew, as an independent person, is privileged to have an incredible, loving, bidirectional relationship with God. Our service stems from a desire to please the Ultimate Being that we love.

While a sheep is certainly less cherished than a child, from a different perspective the sheep-shepherd relationship runs even deeper than the child-parent. Of all animals, sheep are characterized by their obedience and submission. A sheep does not heed the shepherd’s call from a desire to please the shepherd, but rather due to its obedient nature. For a Jew, this level of self-negation (bittul) stems from the realization of ain od milvado, that nothing, especially one’s soul, exists outside of God. Therefore, we are truly not independent entities and have no will outside of God.

These two levels of connection to God are associated with two different forms of service. Torah study corresponds to the level of the child. The strong intellectual effort that is expended on Torah study highlights the reality of the studier as an independent person with an autonomous and creative mind. Also, it is through Torah study that we recognize God’s grandeur, which generates our love for Him and desire to please Him. In this sense, we are similar to the child seeking to please his “great” parent whom he loves.

The self-negation of a sheep rises to the fore when we are involved in actional mitzvot intended to purify the world. The Hebrew word for sheep, zon, is etymologically connected with the word Hebrew word yezi’ah or “going out.” The mission of purifying the world requires one to leave the spiritual sweetness of the study hall and “go out” to be physically involved with the less “spiritual” broader world. This transition entails a double descent: from the study hall to the outside world and from a focus on one’s more “spiritual” intellectual faculties to an involvement in the world of action. For the average person interested in developing a bidirectional relationship with God, such a shift would be assessed as a spiritual regression.

It is only a person who is completely nullified to God that will be willing to sacrifice his own feelings of spirituality for the sake of God’s mission.[25] It is this kind of selfless service that most fully creates the dirah be-tahh’tonim (dwelling place in the lowest realms) for God.[26]

This, then, explains the course of Yaakov’s life. He begins as a son of God who studies Torah in the tents of Shem and Ever, far from the troubles and travails of the world. But it is only after “va-yeizei Ya’akov,” when Yaakov leaves his familiar spiritual surroundings and goes to Haran that he develops the deeper connection with Hashem through bittul. It is paradoxically not the study of Torah per-se, but rather his honesty and integrity in business and the actual performance of the six hundred and thirteen commandments in Lavan’s house that allows Yaakov and the whole world to achieve the ultimate connection with Hashem. It is for this reason that sheep, symbolic of the service through self-nullification, become the leitmotif in Yaakov’s life after leaving his father’s home.

The Rebbe concluded that this lesson is particularly pertinent in this generation:

The Lubavitcher Rebbe further emphasizes that this newfound focus on action for the sake of illuminating the lowest aspects of the world needs to be characterized by the utmost sense of self-negation:

For the Lubavitcher Rebbe, this emphasis on ma’aseh affects even the motivation and mode of Torah study. In the ideal messianic setting, one’s learning does not only express an autonomous and creative mind, but must simultaneously and paradoxically be executed with a complete sense of bittul, which generally typifies action.[28] The unification of these seemingly antithetical modes of worship can only occur when the deepest essence of the neshama is accessed, a level that is associated with the messianic era.[29]

The Lubavitcher Rebbe saw this shift toward “ma’aseh gadol” as part of a more general recalibration in emphasis of our avodat Hashem as we approach the messianic era. Many of the ideas that were previously esoterically expressed in Habad’s voluminous literature were not only expansively and innovatively developed by the Rebbe during his forty year tenure as Habad’s leader, but also took on greater physical and practical form.

May we merit to properly serve God with our minds, hearts and actions.

[1]Guide to the Perlplexed, 3:54. Translation from Shlomo Pines, Guide to the Perplexed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), 635.

[2] Marvin Fox, Interpreting Maimonides (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990), 316-317; Norman Lamm, Torah Lishmah: Torah for Torah’s Sake in the Works of Rabbi Hayyim of Volozhin and his Contemporaries (Hoboken, New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House; New York, Yeshivah University Press, 1989), 143; Menahem Kellner, Science in the Bet Midrash: Studies in Maimonides (Brighton MA: Academic Studies Press, 2009), 63-80. See Guide to the Perplexed, 3:27 where this point is made most explicitly. Lamm, Torah Lishmah, 174 notes that his assertion that Rambam unequivocally favors intellectual enlightenment to observance of the halakhic system is challenged by Dr. Isadore Twersky in his Introduction to the Code of Maimonides.

[3] Yesodei HaTorah 4:8

[4] Guide to the Perplexed 3:8 (Pines, 431).

[5] Guide to the Perplexed 2:56 (Pines, 371) and 3:8.

[6] All of Section 4 of Nefesh ha-Hayim is dedicated to the nature and significance of Torah study. For R. Hayim’s understanding of the relationship between Torah study and the fulfillment of actional mizvot, see 4:29-30. For analysis and contextualization see Lamm, Torah Lishmah, 153-154.

[7] Tanya, Likkutei Amarim, chapter 5. Translation from http://www.chabad.org/library/tanya/tanya_cdo/aid/1028886/jewish/Chapter-5.htm.

[8] See Moshe Halamish, Mishnato ha-Iyunit shel R. Shneur Zalman mi-Liadi, Dissertation (Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, 1976), 244-272 for an elaboration on many of these themes.

[9] Tanya, Likkutei Amarim, chapter 1.

[10] Tanya, Likkutei Amarim, chapter 35. Translation from http://www.chabad.org/library/tanya/tanya_cdo/aid/1029034/jewish/Chapter-35.htm.

[11] See, also, Tanya, Iggeret ha-Kodesh, epistle 5.

[12] Torah Ohr, Ester, 120b.

[13]Tanya, Iggeret ha-Kodesh, Epistle 9. Translation from http://www.chabad.org/library/tanya/tanya_cdo/aid/1029292/jewish/Epistle-9.htm. See, ibid, Epistle 5 for the explanation of why charity in particular is the paradigmatic actional mitzvah.

[14] It is interesting that a parallel to this historical shift can be found in the individual person. There is a tannaitic debate (Kiddushin 40b) regarding which of Talmud or ma’aseh is “greater.” Shitah Mekubezet, Bava Kamma 17a cites the opinion of R. Yeshaya that during one’s youth, Talmud is greater, but “in the end of a person’s life” we assume that ma’aseh is greater.

[15] It is passages such as these that presumably served as sources for Rav Kook’s perspective that certain emphases in the service of God need to be recalibrated as the messianic process accelerates. See my recent article “’She Should Carry Out All Her Deeds According To His Directives:’ A Halakha in a Changes Social Reality” at Lehrhaus for a case study and brief elaboration on this theme in the thought of Rav Kook.

[16] See Jerome Gellman, “Zion and Jerusalem” in Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook and Jewish Spirituality ed. Lawrence Kaplan and David Shatz (New York: New York University Press), 288 who lists fourteen distinct places where this idea appears in the thought of the Alter Rebbe.

[17] Habad Hassidism never shied away from a dialectical embrace of seemingly contradictory notions, and in fact, these paradoxes are at the core of the Habad world view. See, Rachel Elior, The Paradoxical Ascent to God: The Kabbalistic Theosophy of Habad Hassidism, trans. Jefferey Green, (SUNY Press, 1992), 33-35 who lists a series of core paradoxes that lie at the heart of Habad doctrine.

[18] Torah Ohr, Parshat Noah, 8c. For an explanation of the terms Hokhmah and Razon see Nissan Dubov, “The Sefirot,” available at http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/361885/jewish/The-Sefirot.htm. Another very relevant primary source appears in his Seder Tefilot mi-Kol ha-Shanah Volume 1, 23a where the Alter Rebbe connects the unique relevance of action for the later generations with the fact that action is rooted in the highest level of divinity. It is also important to note that the performance of mizvot in this system is an end unto itself and not a means towards a higher goal as there can be no further regression beyond God’s Will. In this regard, see, Likkutei Sihot Volume 6, pg. 21-22 and notes 69-70 there.

[19] It is important to note that the relationship between Torah study and action in the thought of the Alter Rebbe is a disputed matter in scholarship. My above presentation follows which did not present the Alter Rebbe as categorically favoring actions over learning is the approach of Moshe Halamish, “Mishnato ha-Iyunit shel R. Shneur Zalman mi-Liadi” 269-271. He marshals many conflicting statements regarding the hierarchy of Torah study and actional mizvot and therefore concludes that in the Alter Rebbe’s final estimation one cannot speak of a true hierarchy but of complementary perspectives. I was recently informed that this is also the internal tradition of Habad Hassidim. However, see Norman Lamm, Torah Lishma, 147-151 and Rivkah Schatz Uffenheimer, “Anti Spiritualizm she-be-Hassidut: Iyunim be-Torat Shen’ur Zalman mi-Liadi” ha-Molad 171-172 (1953): 513-528 who assert that that ultimately the Alter Rebbe gave action a higher place in the spiritual hierarchy than Torah study. In this regard it is enlightening to read the siha of the 7th Lubavitcher Rebbe (Likkutei Sihot, Volume 8, 186-191) who proposes that while only actions can draw down from the “essence” of God, Torah study is necessary in order to reveal the “Divine essence” in this world.

[20] See Avot, 1:17. Also, regarding the tannaitic debate (Kiddushin 40b) if Talmud or ma’aseh is “greater,” see Sefer ha-Ma’amarim 5747, pg. 58 where the Rebbe posits that throughout most of history the ruling has been on the side of Talmud (though, see Rashi, Bava Kama 17a s.v. meivi lidei), in the times of Mashiach the Sanhedrin will reverse the ruling and decide that ma’aseh is “greater.” See there for a longer analysis.

[21] It is interesting that the Vilna Gaon also spoke of the increased significance of action as part of the messianic process, as least in regard to the “ma’aseh” of settling the Land of Israel. See, Kol ha-Tor chapter 1 and Refael Shohat, Olam Nistar be-Mamadei ha-Zeman: Torat ha-Geulah shel ha-Gra mi-Vilna, Mekoroteha, ve-Hashpa’atah le-Dorot (Ramat Gan: University of Bar Ilan Press, 2008), 239-242. Rav Kook (Shemonah Kevazim 3:92), as well, discusses the newfound crucial nature of “ma’aseh,” in the form of engaging worldly affairs, during the era preceding the coming of Mashiach.

[22] For a longer discussion of this topic see R. Feital Levin, Heaven on Earth: Reflections on the Theology of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menahem M. Schneerson (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot Publishing Society, 2002), 114-122; Yizhak Krauss, ha-Shevi’i – Meshi’hiyut be-Dor ha-Shevi’i shel Habad (Tel Aviv: Yedi’ot Ahronot Books, 2007), 137-143.

[23] Likkutei Sihot Volume 15, 252-258.

[24] Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah 2:16.

[25] For a detailed elaboration of the various levels of mizvot in the thought of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, see Gidran shel Mizvot, Hukim u-Mishpatim be-Mishnato shel ha-Rebbe, compiled by R. Yoel Kahn (Brooklyn, NY: Kehot Publication Society, 1994). The highest level of the performance of mizvot in the state of complete bittul is discussed there, pp. 38-43.

[26] The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s association of actional mizvot with complete bittul to God and the study of Torah with a human being’s independent and autonomous nature is a study in contrasts with the approach of Rav Soloveitchik. See, Maimonides: Between Philosophy and Halakha: Rabbi Joseph b. Soloveitchik’s Lectures on the Guide to the Perplexed at the Bernard Revel Graduate School (1950-1951) edited, annotated and with an introduction by Lawrence J. Kaplan (Brooklyn, NY: Ktav Publishing; Jerusalem, Urim Publications, 2016), 234-235 where Rav Soloveitchik associates the study of Torah with “ontic identification with God,” and the fulfillment of actional mizvot with “the expression of my consciousness of ontic separation [from God].”

[27] Translation is adapted from http://www.chabad.org/therebbe/article_cdo/aid/2295019/jewish/A-Knowing-Heart-Parshas-Vayeitzei.htm.

[28] See the following Ma’marim which express this notion: Marg’la be-Phumeih de-Rava, 5740, sections 7-10; ve-Avdi Dovid 5746, sections 4-5. See also, Torat Menahem, 5719 (volume 25), 275-279; 283-285 for a description of the study of Torah that draws the Divine essence into the world.

[29] For an elaboration on this theme, see R. Yoel Kahn, “Hein ke-Vanim, Hein ka-Avadim” in Ma’ayanotekha le-Mah’shevet Habad 2 (Tamuz, 5764): 2-8; “u-She’avtem Mayim be-Sasson” in Ma’ayanotekha le-Mah’shevet Habad 45 (Tishrei, 5776): 2-7. See also, the above siha about Yaakov, section 6 where the Rebbe describes the necessity for even actions to be intermixed with aspects of the worship of a “son.”