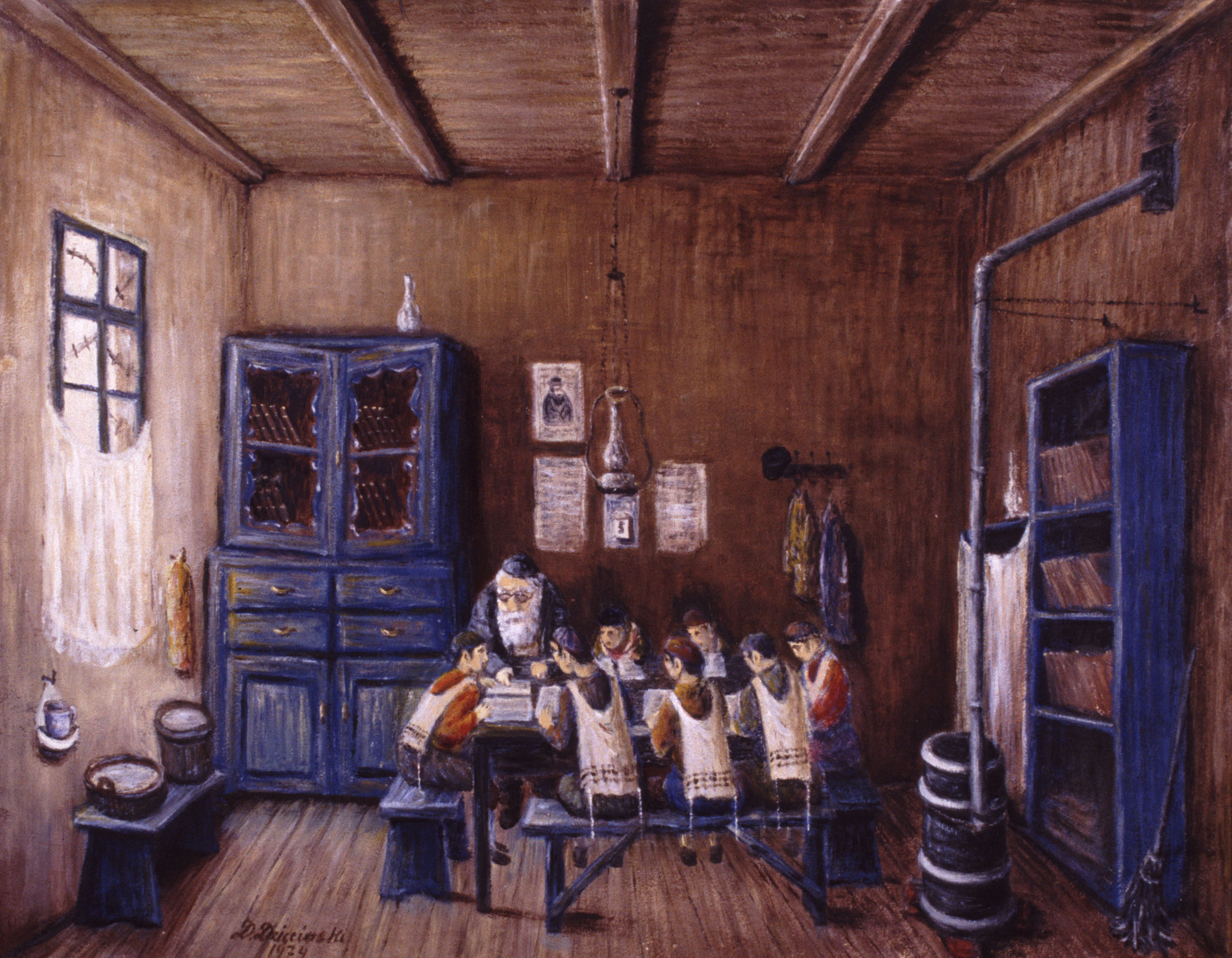

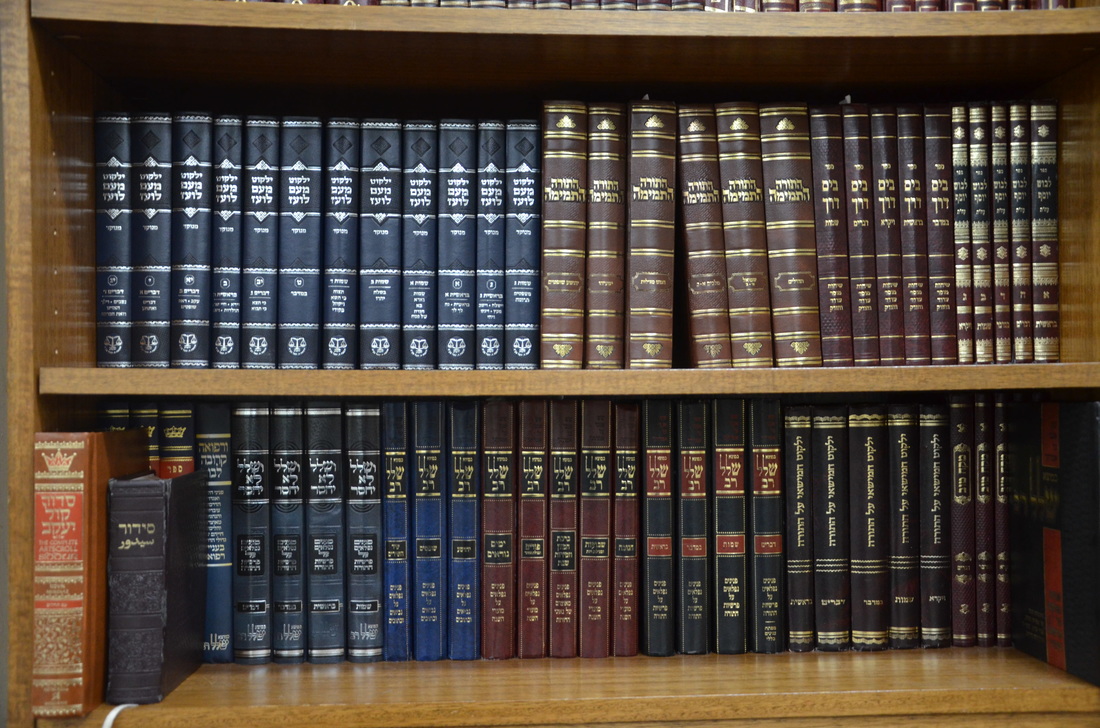

The first historically known beit midrash probably began during the era of the Second Temple. The Pharisees, unlike the Sadducees, emphasized that Torah learning, and not only temple service, was a vital aspect of Jewish life. Thus, physical centers of Jewish learning slowly became the heart of Jewish living.[i] But there is another first beit midrash—the beit midrash of Rabbinic literature, the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber.

The Torah lists Noah’s three sons as Shem, Ham, and Japheth. Genesis Rabbah questions this order, knowing that Shem was not Noah’s eldest son from later verses[ii]. The Midrash then answers this question, explaining that Shem was honored and mentioned first because of his own personal righteousness and the greatness of his descendent, Abraham (Gen. Rabbah 26:3). The Midrash knows that Abraham was the descendent of Shem from family trees listed later in the Torah. The belief that Shem was righteous probably stems from the story of Noah’s drunkenness (Gen. 9:20-27). Walking backwards, Shem and Japheth covered their father’s body during his drunken state in order to not look upon his nakedness. When Noah awoke he said, “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Shem. Let Him [God] dwell in the tents of Shem” (Gen. 9:25-26)[iii]. The Midrash interprets this blessing to mean that the shekhinah (God’s presence) will only dwell in the tents of Shem (Gen. Rabbah 36:8). Though the blessing itself may be referring to future generations and the tents within the verse are not necessarily connected to Torah study, this verse probably serves as the Midrash’s inspiration for the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber (Shem’s son).

The Midrash refers to the influence of Shem and Eber on numerous occasions. Each time, Shem and Eber appear as the spiritual guides of the forefathers and mothers. Malki-Tsedek, the priest who blesses Abraham, is in fact identified as Shem (Gen. Rabbah 44:7). Genesis 25:22 describes Rebecca’s pregnancy, explaining that “the children struggled in her womb.” To understand this abnormal occurrence, she “went to inquire of the Lord and the Lord answered her” (Gen. 25:23). The Midrash here explains that she went to the beit midrash of Shem and Eber. The Midrash similarly claims that conversations that Sarah and Hagar had with God took place through the mediation of Shem (Gen. Rabbah 45:10, 48:20). However, Shem and Eber are not merely intermediaries between man and God; the Midrash explains that they were figures of justice as well. In the Midrashic read of the story, Esau feared killing Jacob because he knew Shem and Eber would judge him for this sin (Gen. Rabbah 67:8).

Finally, Shem and Eber are presented as teachers. After the akeidah, Abraham sent Isaac to learn Torah from Shem (Gen. Rabbah 56:11). Rashi, quoting the Talmud, says that Jacob also studied at the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber for fourteen years before he came to the house of Laban (Megilla 17a). The Midrash teaches that Jacob taught everything he had learned from Shem and Eber to his son, Joseph (Gen. Rabbah 84:8). In addition to the sources in Genesis Rabbah, Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah states that one who studies Torah in this world will be brought to the beit midrash of Shem, Eber, Abraham, Isaac, Moses, and Aaron in the world to come (Shir ha-Shirm Rabbah 6:2).

The various references of the sages to the beit midrash of Shem and Eber are puzzling. What prompts the sages to reference the beit midrash at these specific moments of the Torah? Furthermore, what is the purpose of these references? Are they merely providing background to the text of the Torah, or do they also enhance one’s understanding of the text itself?

Understanding the purpose and the development of Midrash may help answer these questions regarding the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber. Rabbi Dr. Isadore Epstein outlines the development of Midrash in his foreword to the Soncino translation of Midrash Rabbah[iv]: When the Jews returned to Israel after the first exile, Ezra gathered them together with the mission of inspiring them to follow the ways of the Torah. “They read from the scroll of the teaching of God, translating it and giving it sense; so they understood the reading” (Nehemiah 8:8). Ezra created a reading of the Torah that explained textual difficulties and was in touch with the current thought and mindset of the time. This was the oral beginning of Midrash. It was based on the belief that each generation could reveal different latent aspects of the infinitely meaningful Torah. Epstein writes, “The Midrash thus created and brought into shape by the Soferim for the purpose of expounding the Torah fulfilled a vital necessity. For centuries after Ezra, it represented the most important medium for the expression of Jewish thought and teaching.”

Upon studying all the Midrashim concerning Shem and Eber, it is evident that they too respond to textual difficulties. For example, the Midrash that says Jacob went to study in the biet midrash of Shem and Eber for fourteen years is addressing fourteen years of Jacob’s life that are left unaccounted for in the text. When the Midrash comments after the akeida that Isaac went to study with Shem and Eber, it is addressing the verse that says Abraham returned to his servants, making no mention of Isaac returning (Genesis 22:19). And when the Midrash explains that Joseph’s father taught him the Torah he learned with Shem and Eber, it is explaining the unusual term, “ben zekunim.” (It comes from the root word elder (zaken) to teach that Joseph was the “son of elders” for he had learned the Torah of these elders.)

But like the Midrash about Rebecca, these Midrashim are also addressing deep theological questions: How did Jacob and Joseph have the strength to live in the homes of Laban and Pharaoh—in exile—and not assimilate? From where did Isaac derive the inspiration to remain a committed Jew after he was almost killed for the sake of God? What was the foundation of the forefathers’ commitment to God?

Hazal’s use of the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber made the struggles of the Avot relevant to Jews of later generations. Jews of Hazal’s time went to batei midrash and Jewish sages to find faith, build relationships with God, and discover inspiration for combating assimilation and hardship[v]. Hazal therefore say that the forefathers went to the righteous elders of their times, Shem and Eber, and learned Torah from them. This Torah learning served as a foundation for the forefathers’ survival of exile. Thus, the stories of the forefathers become relatable archetypes of Torah dedication. A struggling Jew in exile can understand the story of Jacob and Joseph and look to them as a relevant role models.

The importance of the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber lies not in its historical accuracy, but rather in its representation of a culture in which one can maintain a relationship with God despite its difficulty. According to the read of the Midrash, God did not simply appear to the Bible’s heroes. They were not born with deep strength and conviction; rather, the forefathers worked hard to develop their faith. They went to seek advice from those who knew more than they. They spent time contemplating God and life’s meaning. A Jew reading the Torah without Midrashim often finds stories foreign to his or her own life. The Torah speaks of leaders hearing God’s voice, erecting alters, and witnessing miracles—living a life that sounds vastly different from the practice of Judaism in the days of Hazal. By stating that one who studies Torah in this world will be brought to the beit midrash of Shem, Eber, Abraham, Isaac, Moses, and Aaron in the world to come, Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah establishes a connection between every Jew and the Bible’s leaders. Learning Torah in a beit midrash is actually as valid a way of encountering God as witnessing miracles. A Jew learning Torah joins the rank of Israel’s greatest leaders in the next world. The midrashim of the beit midrash of Shem and Eber allow Jews to view the forefathers as applicable paradigms of the effort and dedication required for cultivating a Jewish life of faith. They allow each Jew who learns Torah to feel like they are following in the footsteps of Tanakh’s greatest figures.

Miriam Pearl Klahr is a sophomore at Stern College and is a staff writer for Kol Hamevaser

[i] “Pharisees,” Jewish Encyclopedia, available at www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12087-pharisees

[ii] Noah started having children at the age of five hundred (Genesis 7:6). Noah was six hundred years old at the time of the flood (Genesis 5:32). Shem was one hundred years old two years after the flood (Genesis 11:10). Therefore Noah must have been five hundred and two years old when Shem was born, and Shem was not Noah’s eldest son.

[iii] All translations are from the JPS Tanakh.

[iv] Rabbi Dr. Isadore Epstein, Foreword in Midrash Rabbah Translated into English, ed. Rabbi Dr. H. Freeman (London, The Soncino Press, 1961), 4-23

[v] “Pharisees,” Jewish Encyclopedia, available at www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12087-pharisees

The First Beit Midrash: The Yeshivah of Shem and Eber

The first historically known beit midrash probably began during the era of the Second Temple. The Pharisees, unlike the Sadducees, emphasized that Torah learning, and not only temple service, was a vital aspect of Jewish life. Thus, physical centers of Jewish learning slowly became the heart of Jewish living.[i] But there is another first beit midrash—the beit midrash of Rabbinic literature, the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber.

The Torah lists Noah’s three sons as Shem, Ham, and Japheth. Genesis Rabbah questions this order, knowing that Shem was not Noah’s eldest son from later verses[ii]. The Midrash then answers this question, explaining that Shem was honored and mentioned first because of his own personal righteousness and the greatness of his descendent, Abraham (Gen. Rabbah 26:3). The Midrash knows that Abraham was the descendent of Shem from family trees listed later in the Torah. The belief that Shem was righteous probably stems from the story of Noah’s drunkenness (Gen. 9:20-27). Walking backwards, Shem and Japheth covered their father’s body during his drunken state in order to not look upon his nakedness. When Noah awoke he said, “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Shem. Let Him [God] dwell in the tents of Shem” (Gen. 9:25-26)[iii]. The Midrash interprets this blessing to mean that the shekhinah (God’s presence) will only dwell in the tents of Shem (Gen. Rabbah 36:8). Though the blessing itself may be referring to future generations and the tents within the verse are not necessarily connected to Torah study, this verse probably serves as the Midrash’s inspiration for the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber (Shem’s son).

The Midrash refers to the influence of Shem and Eber on numerous occasions. Each time, Shem and Eber appear as the spiritual guides of the forefathers and mothers. Malki-Tsedek, the priest who blesses Abraham, is in fact identified as Shem (Gen. Rabbah 44:7). Genesis 25:22 describes Rebecca’s pregnancy, explaining that “the children struggled in her womb.” To understand this abnormal occurrence, she “went to inquire of the Lord and the Lord answered her” (Gen. 25:23). The Midrash here explains that she went to the beit midrash of Shem and Eber. The Midrash similarly claims that conversations that Sarah and Hagar had with God took place through the mediation of Shem (Gen. Rabbah 45:10, 48:20). However, Shem and Eber are not merely intermediaries between man and God; the Midrash explains that they were figures of justice as well. In the Midrashic read of the story, Esau feared killing Jacob because he knew Shem and Eber would judge him for this sin (Gen. Rabbah 67:8).

Finally, Shem and Eber are presented as teachers. After the akeidah, Abraham sent Isaac to learn Torah from Shem (Gen. Rabbah 56:11). Rashi, quoting the Talmud, says that Jacob also studied at the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber for fourteen years before he came to the house of Laban (Megilla 17a). The Midrash teaches that Jacob taught everything he had learned from Shem and Eber to his son, Joseph (Gen. Rabbah 84:8). In addition to the sources in Genesis Rabbah, Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah states that one who studies Torah in this world will be brought to the beit midrash of Shem, Eber, Abraham, Isaac, Moses, and Aaron in the world to come (Shir ha-Shirm Rabbah 6:2).

The various references of the sages to the beit midrash of Shem and Eber are puzzling. What prompts the sages to reference the beit midrash at these specific moments of the Torah? Furthermore, what is the purpose of these references? Are they merely providing background to the text of the Torah, or do they also enhance one’s understanding of the text itself?

Understanding the purpose and the development of Midrash may help answer these questions regarding the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber. Rabbi Dr. Isadore Epstein outlines the development of Midrash in his foreword to the Soncino translation of Midrash Rabbah[iv]: When the Jews returned to Israel after the first exile, Ezra gathered them together with the mission of inspiring them to follow the ways of the Torah. “They read from the scroll of the teaching of God, translating it and giving it sense; so they understood the reading” (Nehemiah 8:8). Ezra created a reading of the Torah that explained textual difficulties and was in touch with the current thought and mindset of the time. This was the oral beginning of Midrash. It was based on the belief that each generation could reveal different latent aspects of the infinitely meaningful Torah. Epstein writes, “The Midrash thus created and brought into shape by the Soferim for the purpose of expounding the Torah fulfilled a vital necessity. For centuries after Ezra, it represented the most important medium for the expression of Jewish thought and teaching.”

Upon studying all the Midrashim concerning Shem and Eber, it is evident that they too respond to textual difficulties. For example, the Midrash that says Jacob went to study in the biet midrash of Shem and Eber for fourteen years is addressing fourteen years of Jacob’s life that are left unaccounted for in the text. When the Midrash comments after the akeida that Isaac went to study with Shem and Eber, it is addressing the verse that says Abraham returned to his servants, making no mention of Isaac returning (Genesis 22:19). And when the Midrash explains that Joseph’s father taught him the Torah he learned with Shem and Eber, it is explaining the unusual term, “ben zekunim.” (It comes from the root word elder (zaken) to teach that Joseph was the “son of elders” for he had learned the Torah of these elders.)

But like the Midrash about Rebecca, these Midrashim are also addressing deep theological questions: How did Jacob and Joseph have the strength to live in the homes of Laban and Pharaoh—in exile—and not assimilate? From where did Isaac derive the inspiration to remain a committed Jew after he was almost killed for the sake of God? What was the foundation of the forefathers’ commitment to God?

Hazal’s use of the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber made the struggles of the Avot relevant to Jews of later generations. Jews of Hazal’s time went to batei midrash and Jewish sages to find faith, build relationships with God, and discover inspiration for combating assimilation and hardship[v]. Hazal therefore say that the forefathers went to the righteous elders of their times, Shem and Eber, and learned Torah from them. This Torah learning served as a foundation for the forefathers’ survival of exile. Thus, the stories of the forefathers become relatable archetypes of Torah dedication. A struggling Jew in exile can understand the story of Jacob and Joseph and look to them as a relevant role models.

The importance of the Yeshivah of Shem and Eber lies not in its historical accuracy, but rather in its representation of a culture in which one can maintain a relationship with God despite its difficulty. According to the read of the Midrash, God did not simply appear to the Bible’s heroes. They were not born with deep strength and conviction; rather, the forefathers worked hard to develop their faith. They went to seek advice from those who knew more than they. They spent time contemplating God and life’s meaning. A Jew reading the Torah without Midrashim often finds stories foreign to his or her own life. The Torah speaks of leaders hearing God’s voice, erecting alters, and witnessing miracles—living a life that sounds vastly different from the practice of Judaism in the days of Hazal. By stating that one who studies Torah in this world will be brought to the beit midrash of Shem, Eber, Abraham, Isaac, Moses, and Aaron in the world to come, Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah establishes a connection between every Jew and the Bible’s leaders. Learning Torah in a beit midrash is actually as valid a way of encountering God as witnessing miracles. A Jew learning Torah joins the rank of Israel’s greatest leaders in the next world. The midrashim of the beit midrash of Shem and Eber allow Jews to view the forefathers as applicable paradigms of the effort and dedication required for cultivating a Jewish life of faith. They allow each Jew who learns Torah to feel like they are following in the footsteps of Tanakh’s greatest figures.

Miriam Pearl Klahr is a sophomore at Stern College and is a staff writer for Kol Hamevaser

[i] “Pharisees,” Jewish Encyclopedia, available at www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12087-pharisees

[ii] Noah started having children at the age of five hundred (Genesis 7:6). Noah was six hundred years old at the time of the flood (Genesis 5:32). Shem was one hundred years old two years after the flood (Genesis 11:10). Therefore Noah must have been five hundred and two years old when Shem was born, and Shem was not Noah’s eldest son.

[iii] All translations are from the JPS Tanakh.

[iv] Rabbi Dr. Isadore Epstein, Foreword in Midrash Rabbah Translated into English, ed. Rabbi Dr. H. Freeman (London, The Soncino Press, 1961), 4-23

[v] “Pharisees,” Jewish Encyclopedia, available at www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12087-pharisees